The telescope's SSD is small compared to what a regular consumer uses, yet its SSD can hold a day's worth of JWST images.

JWST's SSD Could Store a Day Worth of Images

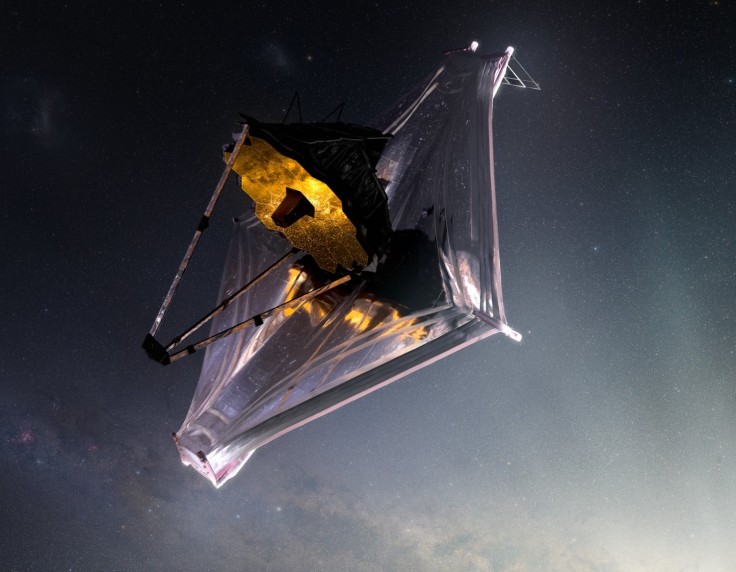

The James Webb Space Telescope, which replaced the Hubble Telescope as the most potent space observatory, is a beautiful instrument. According to IEEE Spectrum, it has an unexpectedly small 68GB SSD, which is just big enough to store a day's worth of JWST photos.

Several stunning photographs captured by the telescope have been provided by NASA, along with image comparisons to its predecessor. But the telescope has a relatively little SSD to store the very detailed pictures, at least in comparison to what the typical customer is accustomed to.

The telescope's 48 Mbps command and data processing subsystem allows it to be virtually filled in as little as 120 minutes while not being nearly as quick as consumer SSDs (ICDH). The JWST can link to the Deep Space Network using a 25.9 GHz Ka-band frequency and send data back to Earth at a rate of 28 Mbps simultaneously.

NASA chose the concept despite being modest for a $10 billion mission. The JWST operates 50 degrees above absolute zero, a million miles from Earth, exposing it to radiation (-370 degrees F). Like all other components, SSDs must be approved and radiation-hardened.

It captures significantly more data than Hubble (57GB vs. 1-2GB per day) but can transport it back to Earth in 4.5 hours. Each 4-hour contact window allows 28.6GB of research data to be sent. The telescope doesn't need to store more than a day's photos.

One mystery remains. NASA anticipates just 60GB of storage will be available after the JWST's 10-year lifetime owing to wear and radiation, and 3% is utilized for engineering and telemetry data storage. We wonder whether the JWST will have the same lifetime as Hubble, which is still running strong after 32 years.

James Webb Telescope's First Image

On July 9, NASA, the James Webb Space Telescope, reached the perfect operating temperature. Engineers completed the scientific calibration of the equipment, and the 21-foot-diameter mirror telescope was operational.

On Tuesday, July 12, a live webcast from NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, released the telescope's first full-color images and spectroscopic data.

The photo exhibited a panorama of "mountains" and "valleys" filled with glittering stars. The edge of the nearby, young star-forming region NGC 3324 in the Carina Nebula may be seen. This picture, which was taken by NASA's brand-new James Webb Space Telescope in infrared light, for the first time makes apparent previously hidden zones of star formation.

Webb's allegedly three-dimensional image, known as the Cosmic Cliffs, depicts what seem to be rocky mountains on a moonlight night. The most significant "peaks" in this picture are the edge of the enormous, gaseous cavity of NGC 3324, which is around seven light-years away.

Intense ultraviolet radiation and stellar winds from massive, hot, young stars situated in the heart of the bubble, above the region seen in this view, have cut the large area from the nebula.

These first pictures from the most giant and most powerful space telescope in the world show Webb at full strength, ready to start its mission of exploring the infrared cosmos.

On Christmas Day, when the James Webb Space Telescope was launched, space enthusiasts were torn between conflicting feelings. Concern about whether the $10 billion machines would successfully attain their goal coexisted with feelings of joy.

A dust-sized micrometeoroid struck one of the primary mirror segments of NASA's pricey James Webb Space Telescope about a month before it was scheduled to begin conducting scientific operations.

Despite the difficulties JWST came along with its space mission, it has successfully delivered to the world a splendid glance at what the universe holds. It was something humanity had been waiting to witness for a long time.